It’s not likely that reading the book of Jeremiah would be something one would recommend for a person confronting a discouraging realization about life and a crisis of faith. But that’s exactly what the ancient prophet Daniel did. The result was nothing short of miraculous.

Daniel was enslaved and in service to the imperial authority from his late adolescence through the end of his life. The book of Daniel takes us through his life, episode by thrilling episode. By the time he prays his prayer in chapter 9, he is well into his eighties. Earlier chapters give us some disquieting insights into the way his life of enforced service to a conquering power impacted his frame of mind.

In the first year of Belshazzar’s reign: “I, Daniel, was troubled in spirit, and the visions that passed through my mind disturbed me” (Daniel 7:15, NIV).

In the third year of Belshazzar: “I, Daniel, was worn out. I lay exhausted for several days. Then I got up and went about the king’s business. I was appalled by the vision; it was beyond understanding” (Daniel 8:27, NIV).

From these verses, we can see that Daniel is deeply troubled by what he has seen in his life. He is exhausted by it. But despite this, he trudges back to work to serve the king. He keeps going—he is, after all, the man who stared down lions. He does what he is required to do, but he is not at peace.

We don’t like to think of Daniel as being troubled and depressed. Our Daniel is brave and stalwart! Well, not always. It seems that, after faithful service to Nebuchadnezzar and then Belshazzar, when yet another overlord, Darius, is introduced into his life, Daniel hits an emotional wall. And then he hits the books.

Seeking to make sense of a world where he has been trapped for as long as he can remember, he goes back to the source. He starts reading the prophecies of Jeremiah. And there he finds the words to describe what is driving his discontent. And he takes that to God in his prayer, which we read in chapter 9.

In the first year of Darius: “I turned to the Lord God and pleaded with him in prayer and petition, in fasting, and in sackcloth and ashes” (Daniel 9:3, NIV).

With the book of Jeremiah’s prophecies in hand, Daniel contemplates the state of his world as the time comes near for the fulfillment of Jeremiah’s prophecy that after an exile of 70 years, Israel will be returned to Jerusalem. However, Daniel realizes that the reasons given for the exile in the first place are even more true than they were when it began, and he begins to doubt whether they will ever be freed from slavery.

If the exile is meant to reform the nation of Israel to be God’s perfect people, then they will never get home! They are doomed to live in slavery forever. The situation is hopeless.

This outlook explains his anxiety and depression. The one thing that has been his source of hope, across a long life of enforced service, seems to be slipping out of his grasp. But now his study of the writings of Jeremiah has given him clarity about what he needs to do next. It is not about hopelessness; it is about clarity—and confrontation.

In anguish he expresses his great sorrow and shame that he and his countrymen are responsible for the terrible situation they are in. “O Lord, righteousness belongeth unto thee, but unto us confusion of faces” (Daniel 9:7, KJV).

Confusion is a synonym for evil in the Old Testament, and when Daniel names what he is feeling as evil, it is not the world around him but the world inside him that he describes. Chaos. Meaninglessness. Confusion. Evil. Not the situation in which the Jewish people are captured, but what is within the hearts and lives of his people, even after 70 years of captivity.

In this epiphany of shame, Daniel includes everyone—from prince to priest to prophet to pauper. “We” he declares. Not one word of defensiveness, but full acceptance of the evil that has flourished among them—which he is now so concerned may interrupt God’s plan, may cancel the rescue operation, may fate the nation to live forever enslaved.

The man who once stood fearless before savage beasts in the lions’ den now acknowledges the inner lions—the lions of shame—that seek to destroy his spirit, his hope, and his faith in God’s plan.

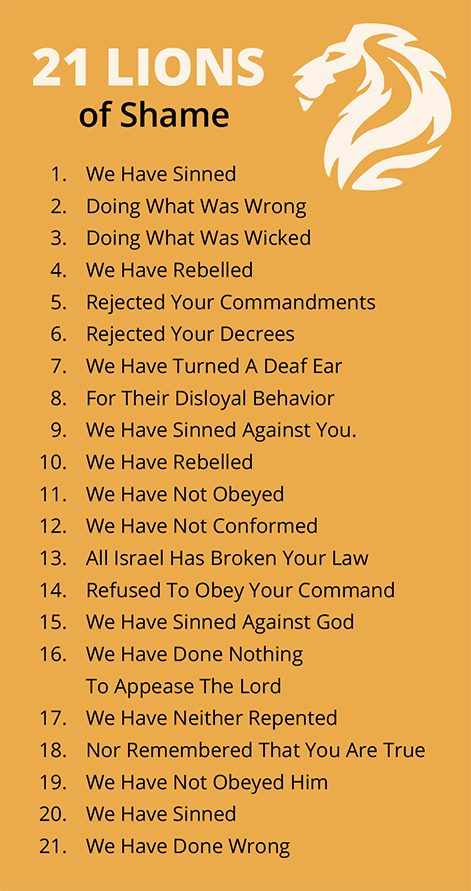

In his prayer, Daniel forcefully describes Israel’s sin as rebellion—the quintessential description of evil. His passionate prayer, in which he describes Israel as sinful—using six different Hebrew words expressed 21 different ways (see sidebar)—is so honest and soul barring that it nearly puts him in his sickbed again.

And then—even though he is exhausted from his litany of shame—Daniel knows he has one more thing he needs to say, one more astonishing set of statements before his prayer is over. He hadn’t gone to the Scriptures to find out how evil the world was or how depraved the sins of Israel had been over their long exile. In the Scriptures he had found nothing about how much the people of God were going to need to change or how that would get out them out of the mess they were in.

In Jeremiah he found the thing that matters most: God keeps His promises. And after enumerating the lions of shame, he pleaded with God to be the God of the prophets and of his greatest hopes: “It is not because of any righteous deeds of ours, but because of your great mercy that we lay our supplications before you. Lord, hear; Lord, forgive; Lord, listen and act” (Daniel 9:18-19, REV).

And God did listen and act. Daniel tells us that as he was praying, Gabriel appeared to him and told him, “You are greatly beloved” (verse 23).

The end of the exile—or end of whatever enslaves us—is not to be realized by focusing on the sins of the world around us or even on our own sins. The end of the exile will come because God keeps His promises and remembers that only He can free us from the lions of shame.

For Daniel, and in the prophecies that were given to both him and Jeremiah, God acts as He has always intended to act.

God’s plan is not deterred by sin or rebellion. Here is what Daniel read in Jeremiah: “’For I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the Lord, ‘plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future’” (Jeremiah 29:11, NIV). The end of sin is not realized by something we do but by something we accept: The acknowledgment that salvation comes from outside of ourselves. The recognition that we are not, in fact, alone. The joyful acceptance of the redemption—the end of the exile—that God offers us.

Like Daniel, we recognize that we must see ourselves as part of a society marked by evil, regardless of how hard we have tried to avoid it. This creates confusion and shame—what can be done? The answer is not in trying harder to do something by ourselves or in creating labels and categories.

The answer, like the one Daniel found in Jeremiah, is to accept the essential and transforming help that comes from God. To know that the help that Providence provides takes practical forms in those people and resources who believe that the divine plan for His world is redemption—and not lives ruined by confusion of face.

The big lie that some theologians tell us is that God is angry with us, and He’s been angry with us since the day we were born. If we repent of our sins, He will change His mind, forgive us, and give us eternal life. But we need to be careful, because if we trip up, God will turn on us at a moment’s notice.

But the great truth is that the love of God for human beings is unconditional. God does not love us because of anything we have done. He does not love us because we are virtuous or obedient or kind. Nor does He cease to love us when we fail to love as we should or when we disobey His commandments. He does not cease to love us even when we commit evil. God’s love for us is unconditional, unmerited, unqualified, unreserved, absolute, immutable. We cannot earn it, no matter how hard we try; we cannot lose it, no matter how hard we try. God does not change His mind. He is eternally in love with the creatures He made in His image.

Daniel knows God is merciful and graceful. Daniel was focused on shame—he could make a long list of sins. What he is praying for is that God will not leave him in shame, with the gulf fixed between Israel’s sinfulness and God’s mercy. Daniel is desperate for God to reach across that gulf. That is what the end of the exile, and the restoration to Jerusalem, really means.

That is what it means to be freed from the lions of shame. Like lions, shame is real. And it can diminish, control, and ruin our lives—if that is all there is. But it isn’t all there is, not by a long shot. “If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins, and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness” (1 John 1:9, KJV).

The fundamental truth of the gospel is that the love of God for human beings is unconditional. There is no lion greater than the Lion of Judah. God does not change His mind, and His purposes are not frustrated by the lions of shame. We are greatly beloved by the one from whom help is on the way and who will forever keep His promises.

_____________________________

Ray Tetz is the director of Communication and Community Engagement for the Pacific Union Conference.